The Giant who ruled Rome

When we think of Roman emperors, we often picture eloquent speakers like Augustus, thoughtful philosophers like Marcus Aurelius, or even lavish party hosts like Nero. However, we seldom imagine a seven-foot giant with hands the size of dinner plates. Meet Emperor Thrax, Rome’s first non-noble emperor, whose life feels more like a subplot from Game of Thrones than a standard story from Roman imperial history.

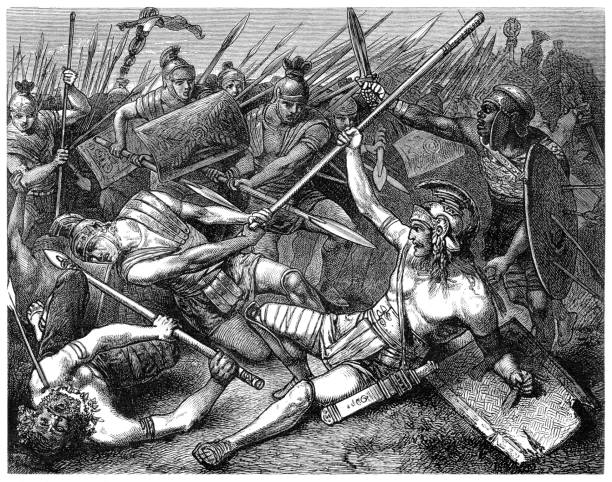

Maximus was born in the Thracian region, which is modern-day Bulgaria. He hailed from a non-aristocratic background; his father was possibly a Gothic shepherd, and his mother belonged to a local tribe. This lineage certainly did not seem like a fast track to the purple toga. What Maximus did possess was his size. Ancient sources describe him as a giant, claiming he was 8 feet tall, though this is likely an exaggeration. It is said that he had such incredible strength that he could pull a fully loaded cart by himself. Regardless of the veracity of these tales, they highlight the formidable reputation he built based on his physical presence. Maximus first gained notice under Emperor Septimus Severus around 200 AD. It is said that he participated in a military parade and famously knocked several soldiers to the ground during a competition, which led to his immediate enlistment.

By 235 AD, Maximus had climbed the ranks to become the leader of a disgruntled army on the Germanic frontier. At that time, Emperor Alexander Severus was viewed as weak and overly influenced by his mother. When the young Alexander attempted to buy peace from the Germanic tribes rather than engage in battle, the legions revolted in anger. They assassinated him and chose Maximus Thrax as their new emperor.

Thus began the reign of Emperor Thrax—the first emperor chosen by the army rather than the Senate or through noble lineage. His ascent also marked the start of the Crisis of the Third Century, a chaotic period characterized by rapid changes in leadership. During his three-year rule, Maximus never set foot in Rome. He preferred to lead from the front lines, surrounded by his troops, rather than deal with the treacherous senators in the capital. This decision led to some significant issues. For one, the Senate despised him. As a provincial of low birth, he paid little heed to their counsel. The Roman elite preferred cultured and articulate emperors over enormous Thracian warriors who reeked of wet leather and battlefield blood. Thrax imposed heavy taxes to fund his military campaigns, believing that force was more effective than diplomacy. If a province was discontented, he sent in troops. If the treasury was depleted, he squeezed the provinces harder. Unsurprisingly, this approach did not endear him to the populace.

Meanwhile, Maximus continued to fight against Germanic and Sarmatian tribes, along with facing discontent from his ranks. He achieved some victories, but dissent began to brew in Rome. In 238 AD, the Senate decided they could no longer tolerate his rule and backed a revolt. In a peculiar and short-lived maneuver, they declared two elderly senators, Gordian and Gordian II, as joint emperors. Both died within weeks, but the rebellion persisted, prompting the Senate to announce new co-emperors. Maximus, unwilling to accept such insubordination, marched toward Italy. However, his army faced logistical issues rather than direct resistance. The city of Aquila refused him entry, leading to a prolonged siege as his troops grew hungry and weary. As morale in Thrax’s army plummeted, his frustrated soldiers took matters into their own hands. In the spring of 238 AD, both Emperor Thrax and his son were murdered by their troops. Legend has it that their heads were severed and sent to Rome, eliciting applause from the senators.

Emperor Thrax’s reign was brief and tumultuous, but it was undoubtedly significant. His story illustrates how fragile imperial power had become and how far Rome had strayed from orderly succession and senatorial decorum. He was the first emperor to rule through military dominance, setting the stage for decades of instability. In some respects, he was ahead of his time—an emperor more soldier than senator. Was he a tyrant? Perhaps. Was he a crude outsider who never fully grasped the intricacies of politics? Almost certainly. He was a man forged in battle, raised by the sword, and for a fleeting, bloody moment, that made him an emperor.

Leave a comment